A significant milestone came in 1920 with the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, which declared that 'the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged… on account of sex'. Since then, the nation’s pursuit of equality has been marked by complexity and contradiction, providing fertile ground for politically minded artists.

Sparked by postwar gender inequities and influenced by the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, America’s ‘Second Wave’ of feminism gained momentum with the publication of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique in 1963 and expanded into broader campaigns for legal, economic, and reproductive rights. American artists such as Barbara Kruger, Martha Rosler and Judy Chicago responded to this social and political climate with experimental work which challenged gender norms, questioned patriarchal structures and created space for marginalised voices.

Justine Kurland

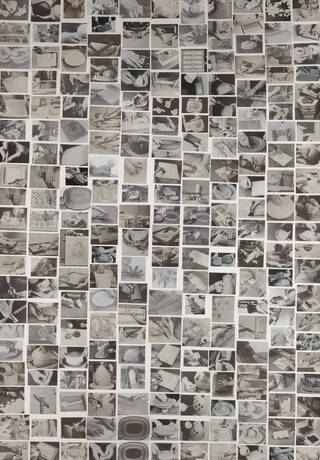

This commitment to change echoes in the work of contemporary artists such as Justine Kurland, whose work seeks to rebalance art’s patriarchal history. Her provocatively titled Nudes (Fisting) (2023), is a large, delicately collaged piece, deconstructed from the pages of Lee Friedlander’s iconic photo book Nudes (1991). In an act of defiant feminism, Kurland’s knife has ‘freed’ these women from a historically objectified gaze, transmuting them into a cascading abstracted shape. It is part of a larger series entitled SCUMB (Society for Cutting Up Men’s Books), which involved Kurland purging her collection of 150 photobooks by the male artists who have monopolised photographic history – a homage to the outrageous manifesto released by Valerie Solanas (the woman who famously shot Andy Warhol) in 1968.

Carmen Winant

The origin of collage can be traced back to folk art and women’s craft – a form of artistic labour often overlooked by art’s gendered hierarchy. Carmen Winant, a proponent of found and everyday photography by unknown or amateur photographers, uses 1970s craft magazines to highlight the dominance of whiteness and the patriarchy in American visual culture. The painstaking process of collecting, cutting and pasting pictures, as seen in her collaged piece Hand Study (Making in Whiteness) V (2021), speaks to her commitment to feminist perspectives and interest in (often unseen and uncompensated) women’s work.

Juliana Beasley

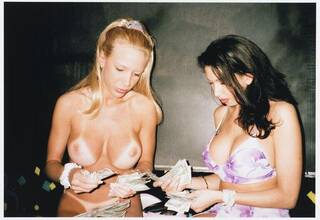

From battling for pay equality, to the hidden cost of childcare and sex work, America’s economic history is filled with the dismissal of women’s contribution to labour and the workforce. Juliana Beasley’s series Lapdancer (1995 – 2002) personally explores this contested (and often invisible) part of economic history. The photographer spent eight years working as an exotic dancer, capturing her colleagues at work and ‘the exchange of love and affection for money’. She left the industry only once she had earned enough to study photography full time.

Anne Collier

Anne Collier’s tongue-in-cheek La femme, la photo et Pentax (2013) pokes fun at the economy of women, both as a consumer and as a subject of the advertising industry. Her appropriated, rephotographed image of a woman holding a camera, ostensibly taking a photograph, is extracted from a French magazine advert from the early 1980s. It poses questions about the power dynamics inherent in marketing tactics, exposing the objectification of (usually) female subjects in commercial print culture, and questioning the agency of women behind the camera.

Doris Derby

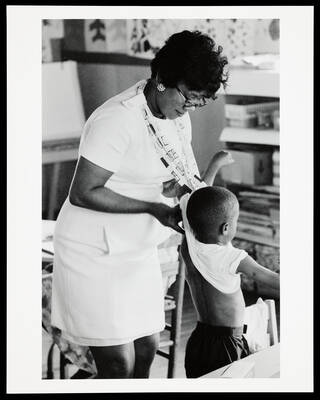

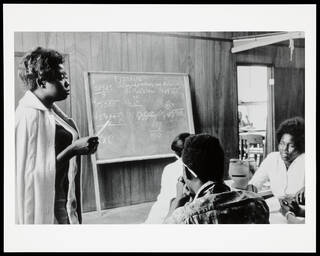

Feminism and activism often go hand in hand. The Black American photographer Doris Derby recorded community and grassroots empowerment efforts in the South during the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. Derby, an educator, activist and documentarian joined the movement in Mississippi in 1963. Her records show Black-owned businesses like the Liberty House handicraft co-operative, and the provision of healthcare and educational programmes. Her work spans gender, but many images centre the contributions of women in the community, such as the administration of care and training at the Tufts Delta Health Clinic.

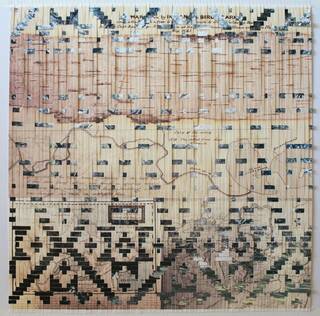

Sarah Sense

Sarah Sense, an American artist with Chitimacha and Choctaw (two distinct Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern United States) heritage, manifests a quiet form of activism in her delicately woven photographs which pay homage to the matriarchal lineage of her family. Using colonial maps of the United States (found in the British Library archives) combined with her own landscape photographs, Sense creates complex artworks which reference Chitimacha basket weaving techniques. Her methods simultaneously deconstruct the fabrication of America’s colonial history, whilst celebrating the empowering craft practices of her female ancestors.

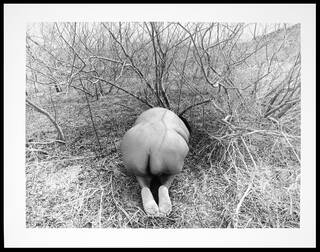

Laura Aguilar

The work of Latina artist Laura Aguilar also addresses America’s complicated relationship to land. Her striking self-portraits are set in the rocky woodlands and deserts of the Southwest, a landscape with hostile connotations for both the Latin and queer community. Aguilar, a prominent LGBTQ+ rights activist, used her work to deconstruct dominant narratives about queer, working class, non-conforming bodies, challenging both racial and feminine stereotypes.

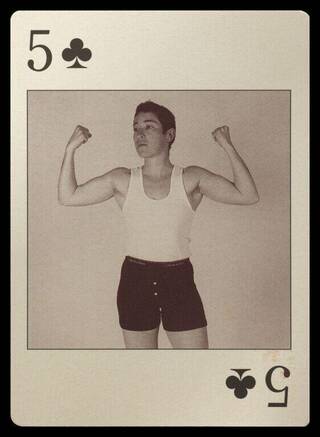

Catherine Opie

The importance of queer perspectives can also be found in Catherine Opie’s ‘Dyke Deck’, which cheekily subverts Lesbian categorisation, offering four ‘types’; ‘couples’ are hearts, ‘jocks’ are clubs, ‘femmes’ are diamonds, and ‘butches’ are spades, a playful yet pointed commentary on representation and belonging.

Kristine Potter

As America’s recent political changes continue to erode civil liberties, threatening the safety of many, including women and the queer community, Kristine Potter’s Dark Waters (2015 – 18) reminds us of the uncomfortable history and persistence of misogynistic violence in America culture. Her gothic photographs evoke the folklore of the American South and the sinister popularity of 19th and 20th century ‘murder ballads’, ominous songs written about the death of anonymous women (usually at the hands of a man). Her photographs of rivers, creeks and deserted dusty trails remind us of the final anonymous resting place of these women, whilst her ghostly portraits centre the female subject, offering one last act of reclamation and commemoration. Potter’s work gives a haunting alternative to the perspectives of American culture, revealing the inherent gender dynamics and power structures imbued within the landscape.

These works can be found in American Photographs, a major new display in The Photography Centre, until 16 May 2027.