As sumō embedded itself into the popular culture of Edo Japan, its leading wrestlers enjoyed celebrity status. Publishers sold woodblock printed portraits, match-day scenes and charts listing wrestlers in order of rank (banzuke) as well as images of wrestlers off duty. These prints drove the sport’s popularity and fed the fame of its stars.

The V&A has an impressive collection of more than 25,000 Japanese woodblock prints, which accounts for about half of the objects in its Japan collection. Around 12,000 of these prints came from one significant purchase made in 1886 from the dealer S. M. Franck & Co. This remarkable body of works reveals the diversity of Japanese prints made in the 19th century. The sumō prints are a small but dynamic part of the collection.

During the Edo period, printmakers produced and sold woodblock prints in vast numbers. A single print might cost no more than a bowl of noodles – these were affordable artworks, bought by the everyday townspeople and pasted onto the walls of their homes.

Sumō prints grew in popularity during the 18th century, alongside the sport’s professional development, and publishers worked with leading artists to capitalise on its interest. In the 18th century, the key artists responsible for sumō prints belonged to the Katsukawa school, such as Shunshō (1726 – 93) and his pupils Shunkō (1743 – 1812) and Shunei (1762 – 1819). The majority of the V&A’s sumō prints date to the 19th century, when the Utagawa school of artists began to dominate the genre, with names such as Kunisada (1786 – 1864), Toyokuni II (1777 – 1835), Kuniteru II (1830 – 74) and Yoshitora (1836 – 80) taking the lead.

The wrestlers

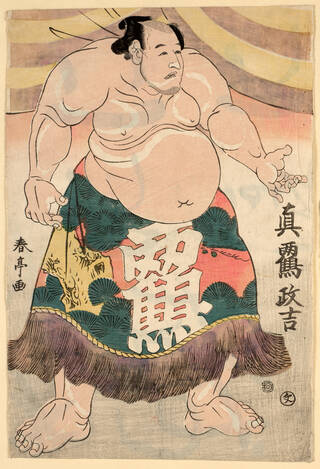

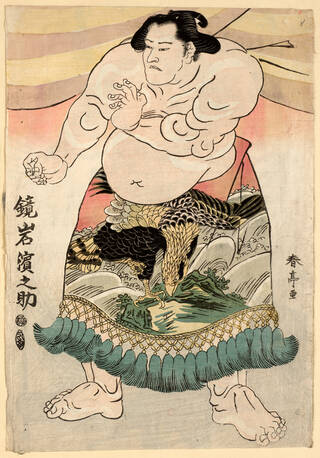

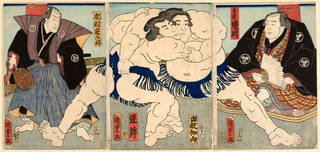

Wrestler portraits were the most popular subjects for sumō prints. Print artists adopted similar conventions to those used to depict popular actors, creating stylised portraits that were nonetheless easy for fans to recognise. By filling the frame of the page, they further conjured an impression of the wrestlers’ formidable size and powerful presence.

Wrestlers are often shown wearing ceremonial aprons called keshō mawawashi. Worn for the ring-entering ceremony at the start of each tournament day, keshō mawawashi were often lavishly embroidered. Wrestlers Kagamiiwa (1769 – 1829) and Manazuru (1775 – 1845) are shown wearing aprons decorated with symbols of strength, with other favoured designs including symbols that identified the wrestlers’ training stable.

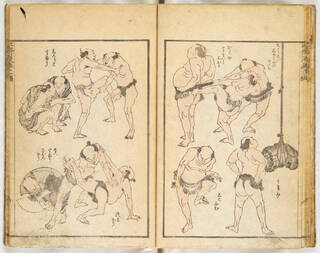

During training and matches, however, wrestlers wear only a mawashi loincloth. A single bolt of fabric, up to nine metres in length, the mawashi is wrapped several times around the waist, hips and under the groin, before being secured in a knot at the back. In an illustration from Hokusai Sketches by Katsushika Hokusai, you can see the effort required to tighten a wrestler's mawashi. For matches, a stiffened frond of matching silk called a sagari is inserted into the mawashi, indicating where an opponent can grab.

Day of the tournament

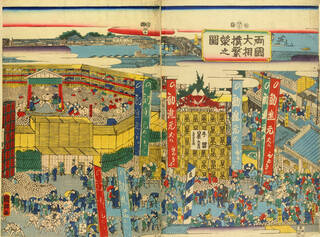

Sumō tournaments were held in temple precincts. To accommodate the crowds, temporary stands were built with seating for up to 3,000 people. The proceeds from ticket sales were generally used for building repairs or other infrastructure projects, such as bridge construction. With low ticket prices, these fundraising matches became hugely popular in Japan’s major cities – Edo (present-day Tokyo), Osaka and Kyoto. From 1833, Ekōin Temple in the Ryōgoku district of Edo became the site for the biannual tournaments held in the capital. A print in the V&A’s collection depicts the view over the temporary stands at Ekōin Temple, revealing the scale of the tournament and its lively atmosphere. Ryōgoku continues to be a centre for sumō in Tokyo today.

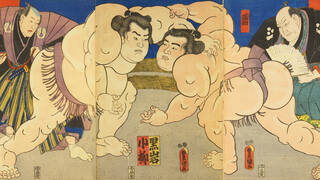

Publishers sold prints depicting matches between top wrestlers. These were typically printed across three sheets of paper allowing a wide panoramic view of the arena or a close-up focus on the action. Typically, the wrestlers appear evenly matched, with no indication of who might win. Publishers were wise to their audiences, and no doubt realised they could double their sales if fans on both sides could be tempted to buy.

A wrestler wins the match by forcing their opponent out of the ring or by causing any part of their body, other than the soles of their feet, to touch the ground. This can be achieved by pushing, throwing, slapping and tripping opponents. The referee (gyōji) umpires the match, keeping a close eye on both wrestlers. In his hand he carries a wooden fan (gunbai), which he raises in the direction of the victor as soon as he sees a winning move. In a reference to sumō’s historical warrior connections, the gunbai resembles signal fans used by Japan’s generals on the battlefield.

Just as sumō’s wrestlers are organised into ranks, there are also eight ranks of referees. A referee’s footwear and fan-tassel colours are decided by their rank. For example, the red and white tassels on a referee’s fan, together with his socks (tabi) indicate that he belongs to the second highest rank, sanyaku. The rank of a referee also decides which matches they can umpire. Only a referee of the highest rank can umpire a match between the highest-ranking grand champions. The coach and head of a training stable (toshiyori) is sometimes shown sat on a cushion beside the ring

Wrestlers as celebrities

Sumō’s top wrestlers enjoyed celebrity status. Here we have three famous wrestlers enjoying fireworks on a summer evening at Ryōgoku bridge, close to Ekōin Temple. While this print may look at first glance like a typical three-sheet print or triptych, it is actually composed of six full printed sheets, set horizontally, and stacked two by three. This unusually large format emphasises the impressive size of these larger-than-life figures.

The wrestlers in this five-sheet panorama below, like those on the bridge above, wear a light cotton summer robe called a yukata. The chequered black and white pattern is popularly known as Benkei jima, or ‘Benkei check’. A warrior monk of the 12th-century, Benkei was renowned for his strength. The plaid pattern became fashionable after it was used for Benkei’s costume in the kabuki theatre play Kanjinchō. The frequent use of this chequered pattern in sumō prints suggests it was a popular choice for wrestlers. The central figure here, Ikuzuki Geitazaemon (1827 – 50), was renowned for being especially tall, standing at a lofty 7 ft 5 in (229 cm).

Fans wanted to know everything about their favourite wrestlers, even details of their private lives. In response, artists depicted wrestlers in their leisure time with imagined views of them going about the city and socialising with each other. Many of these ‘off-duty’ wrestler prints show dining scenes, suggesting that there was a particular curiosity over the diets of wrestlers.

From fashion to fiction

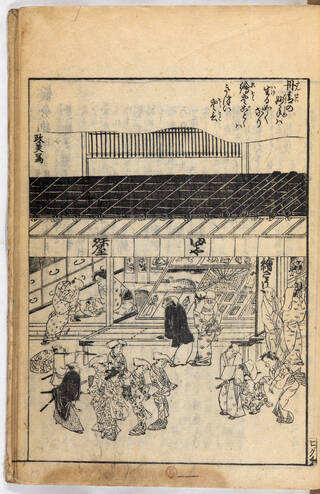

The series of prints below matches a number of top wrestlers with various shops from Edo’s thriving fashion industry. The small inset pictures in the upper left of each print show one of the city’s kimono stores. The kimono store depicted in the second print is Mitsui Echigoya, which still operates as the department store Mitsukoshi. Whether this series represents celebrity endorsement or a publisher’s smart deal is uncertain, but just like sports personalities today, wrestlers could also be fashionable figures.

Another interesting detail shown in the prints is the pair of swords carried by each wrestler. During the Edo period, carrying paired swords was a privilege usually limited to the warrior class. However, sumō had fans in the highest ranks of society, and the best wrestlers were sometimes hired as bodyguards by feudal lords. As a lord’s retainer, these wrestlers were allowed to wear two swords, equivalent to a samurai.

The wrestler Narukami Katsunosuke is a sumō bodyguard who features in the kabuki play Sugawa no hana Azuma no datezome. In the story, which is based on real events, a feudal lord is attacked on a bridge, escaping thanks only to his sumō wrestler retainer.

In the print below we can see the character Narukami wearing a blue kimono decorated with the thunder god, swirling clouds and bolts of lightning. Although the actor portraying Narukami is not named in the print, theatre fans would be quick to recognise him as Arashi Rikan III (1812 – 63).

Prints showing actors in their roles but unnamed became popular in the early 1840s when authorities banned the depiction of kabuki actors. While enforcement of these rules had relaxed by the time these prints were published in 1855, such playful pairings persisted. Each of the prints in this series hides a popular actor in plain view.

The V&A’s collection of Japanese prints offers an enticing glimpse into the world of sumō as it flourished during the Edo period. From fabrics and food, to theatre and fundraising, sumō was a dynamic part of city life and popular culture. As a professional sport enjoyed by the masses, these prints document an exciting period in the long history of Japan’s national sport.